COVID UPDATE: The Comings and Goings of Delta and now, Delta+

When I last wrote about the epidemiology of Covid-19, there were worrisome predictions made about the future case load in the U.S. made by some of our best experts, including Dr. Frances Collins from the NIH. In mid-August, the U.S. was averaging 165,000 new cases per day, and he and other experts stated that we would exceed 200,000 per day by mid-September. Also noteworthy at the time was the confounding incidence of daily new case trends in the U.K.– the vast majority of which were Covid-19 delta - that contrasted sharply with what we saw in India. As a reminder, cases in India rapidly rose earlier in the year, and then rapidly descended at the same rate, forming a narrow bell-shaped curve. Though genetic signature data is lacking relative to U.K., it was generally assumed that the delta variant was the culprit in India.

In the U.K., we at first saw a similar pattern of declines following the delta peak, but that began to reverse back upwards only two weeks later. As of today, the number of daily cases of Covid in the UK is back up around 45K vs. the peak of 55K in mid-July. When the delta cases in the UK first began to descend, the daily case load dropped down to about 30K. The UK is now at 45k, meaning the number of daily cases has risen by 50% over the past 2 months. Interestingly, the rate of increase is far lower than we what saw when delta cases rapidly rose beginning in early June.

This reversal in fortune has occurred despite the UK being in the vanguard of widespread inoculation, with now about 79% of all people over the age of 12 fully vaccinated against Covid. What’s unique about the UK is that it almost exclusively used the homegrown vaccine from AstraZeneca/Oxford. The Astra/Oxford vaccine was the first to be approved in Europe, and the UK was eager to use whatever was its disposal to put an end to the Covid pandemic.

In other west European countries, it was the mRNA vaccines that were ultimately preferred. In the US, it wasn’t just preference for mRNA - the FDA never approved the Astra vaccine because of its lower efficacy and risk of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Recall that there were temporary periodic clinical holds in numerous European countries on usage of the Astra/Oxford vaccine because of the thrombosis observations that proved fatal in some cases. Those halts in vaccinations gave the mRNA vaccines time to be introduced in Europe, so that the Astra/Oxford vaccine ultimately became a second-tier choice. Below is a chart of how daily new cases numbers in the UK have fared to those in France:

It is tempting to blame the reversal of new Covid cases on the lower efficacy of the Astra/Oxford vaccine. But other factors must be at play. All vaccines’ immunoprotection wane over time and since the UK was the earliest in administering the vaccine, one could predict that the British populace is on the leading edge of this waning protection. Another possible contributing factor is the fact that most schoolchildren in the U.K. were allowed to return to school without a mask mandate. Finally, a new variant has emerged in the U.K.: “Delta+”.

Over this past weekend, Dr. Scott Gottlieb expressed his concern about Delta+ on Twitter and recommended that research should immediately be done to gain a better understanding of the incremental danger – if any – that this latest variant poses. As of this writing, experts in the UK estimate that 8% of new cases are caused by the Delta+ variant. During the height of the original delta wave however, it was assumed that over 90% of new cases were caused by the original Delta virus. Also, early indications are that Delta+ is only 10% more transmissible that its delta precursor. The relatively low percentage of Delta+ cases, and the only marginally more transmission potential suggest that the rising cases in the UK can’t all be ascribed to the emergence of this new variant. In Europe, it is not just the UK that has seen a reversal of Covid cases following the initial dip in Delta-driven cases. In the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany, the post delta wave dip has reversed and again begun to climb:

In the U.S., the trends in daily new case rates have proven very encouraging, with the trailing 7-day average of 79,000 now more than 50% lower than the peak of 166,000 reached in early September and showing no sign of decelerating as it moves down further. It turns out that Dr. Francis Collins was prescient in his mid-August prediction that the US would reach 200,000 new Covid-19 cases within a few weeks. On August 27, the U.S. reported 196,838 new cases. Fortunately, that represented the peak.

While some parts of Europe are seeing an uptick in cases, France and Italy have shared with the U.S. a very similar downward trajectory in the daily Covid-19 cases.

The emergence of Covid-19 variants, controlled by a range of vaccines and disparate social safety measures, have combined to form a more complex picture of case trends in Western Europe and the United States. For now, the U.S. is clearly on the mend, so much so that some are predicting that the delta wave represents the final hurrah for Covid-19. We would all like that to be true, but based on what we see in new daily case trends in the U.K., Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, it is perhaps premature to make that call.

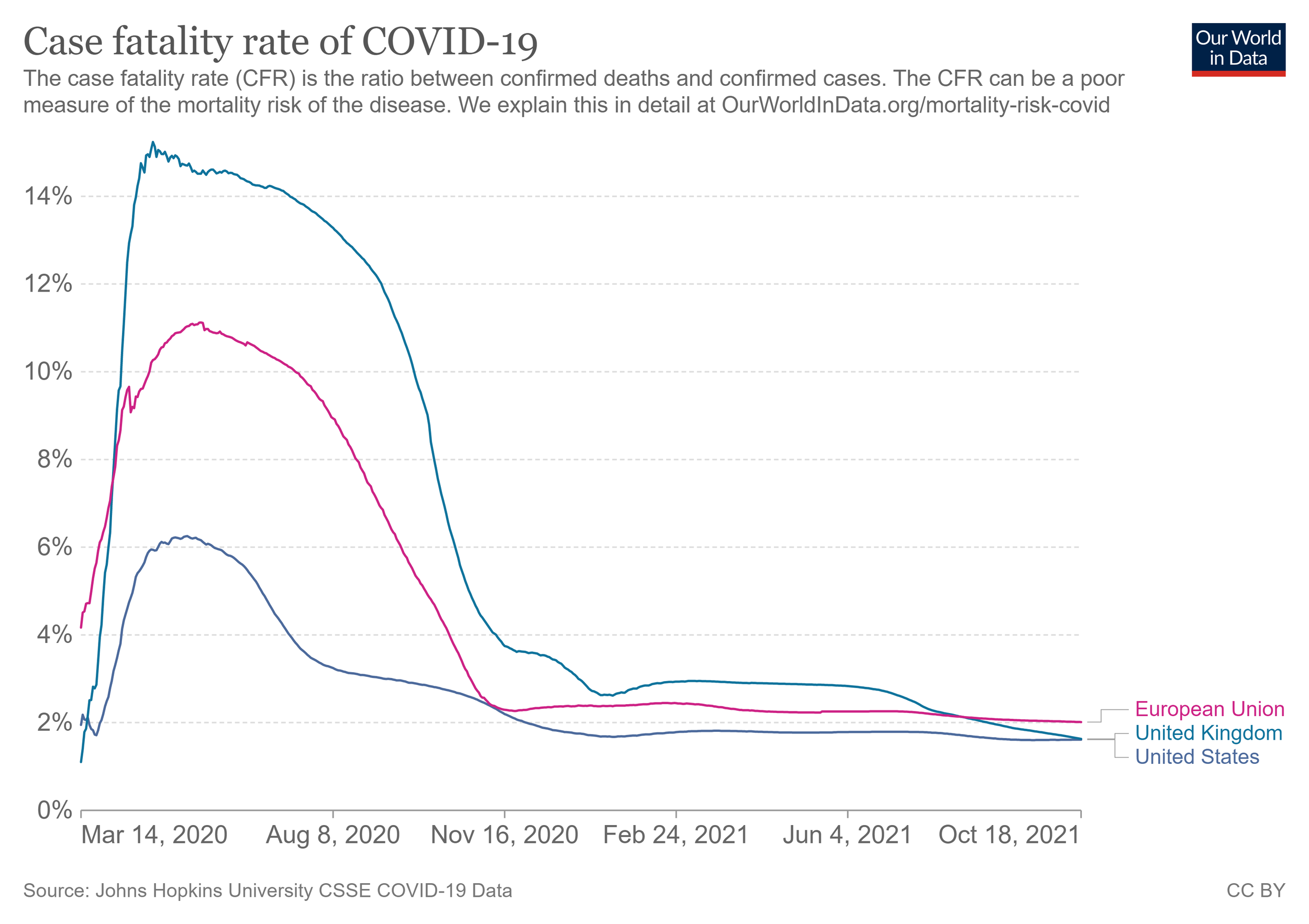

The one very consistent and positive trend in the data - and arguably the most important- is how far down the case fatality rate of Covid-19 has fallen in Europe and in the U.S., despite the varying vaccination rates and choices of vaccines. The chart below illustrates the dramatic impact that vaccination programs have had in tempering the public health effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. Even in the U.K. (top green line), where daily new cases are on the rise, the fatality rate continues to fall and is now below that of the European Union. As long as our vaccine makers can adapt their vaccines to the next variant - which they say is relatively easy to do - there is every reason to believe that while cases might rise and fall, deaths and severe illness from Covid-19 should never again rise to the levels we’ve seen in the past 18 months.